Project-based learning is a powerful method to engage students in deeper learning of academic content while also teaching skills like communication, teamwork and problem-solving. But sometimes it can be hard to envision how it will work in your own classroom. Our advice? Put the students in charge and watch what they come up with!

That’s what we did at the Thomas A. Edison Career & Technical Education High School in New York. We serve a diverse population of 2,400 students in Queens, and our school has become highly sought-after because of our focus on career and technical education and project-based learning. Most of our teachers are trained in the Gold Standard Project-Based Learning model by PBLWorks. We bring what is working in CTE into the academic areas through innovative, student-led projects.

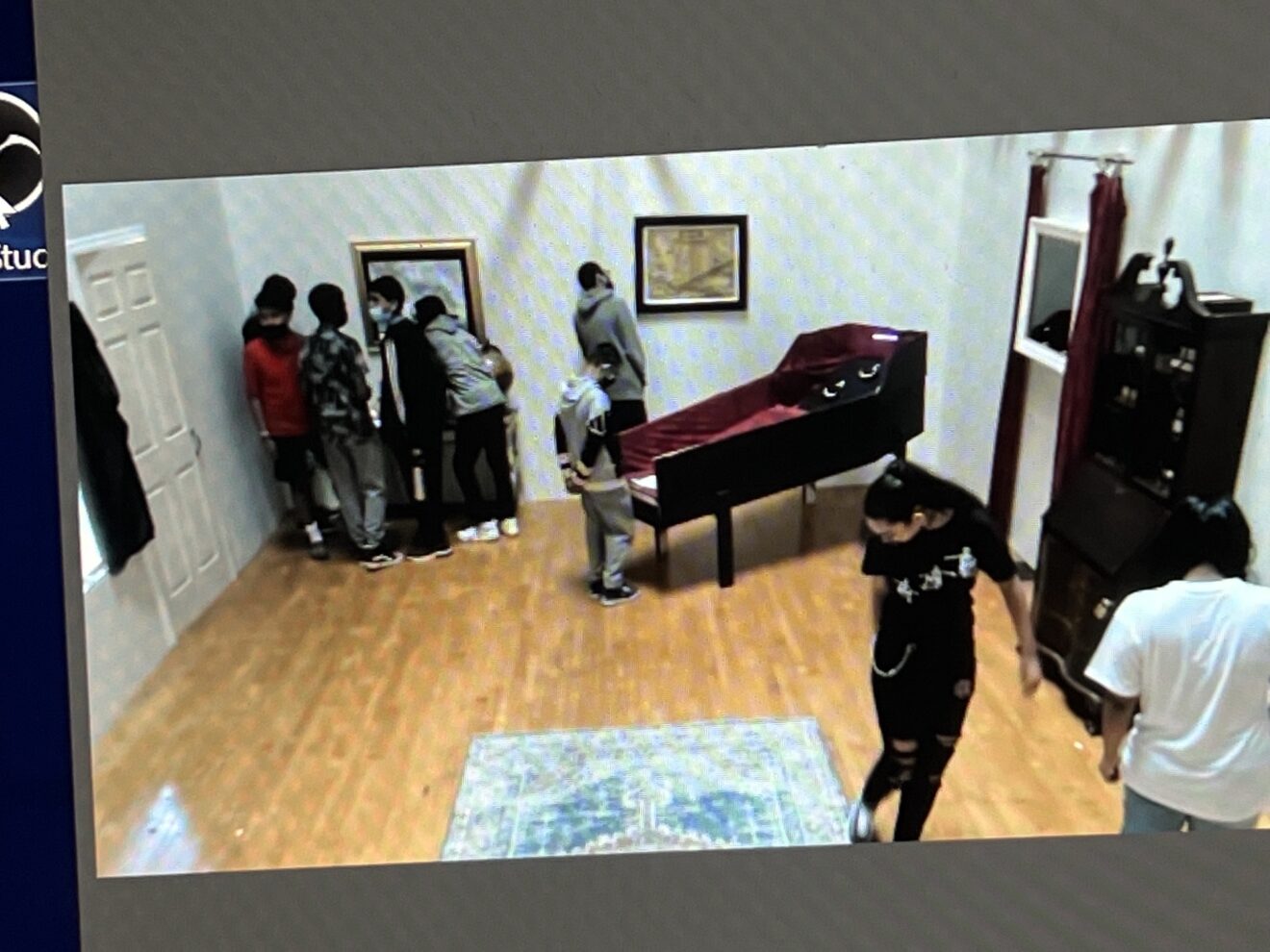

One project we’re particularly proud of is our “Dracula”-themed escape room — a student-devised, student-built, working escape room. It took three years from inception to completion and was ultimately showcased to students, families and communities. It was also used as a team-building experience for teachers and even our school security team and central administration, as well as the New York City Department of Education and the NYC Division of Instructional and Information Technology.

Here’s how we did it and why it was such a powerful project to support deeper learning.

An idea for project-based learning is born

At our school we have a shared leadership model. We essentially treat students as our clients. We ask them to provide their feedback, voice their concerns and share their ideas on topics ranging from curriculum to school culture. In this case, a group of students who at the time were mostly sophomores shared why they were engaged in their CTE courses and why they struggled in their regular academic courses. They provided feedback on instruction and proposed the idea of making history an interactive experience by creating an escape room.

We, of course, asked them for more to kick off the project-based learning project. We asked them to do research to prove why this escape room was a necessary part of their education. They brought us surveys from the New York City school system showing student engagement was only 60% to 70%. They drove the point home that this project could be a fix. They put together a plan where the students and the academic teachers would work together to create the project around academic content. It would be a fun way to learn the content while also building other hard skills like carpentry, coding and engineering. Once we gave the green light, they worked with the English language arts teachers to solidify the theme and decided to focus the escape room on the novel “Dracula.”

Here’s how the escape room project came together and the project-based learning skills that evolved as a result.

Step 1: Research. Students went on a field trip to an escape room and interviewed the person who invented that particular room. They asked questions that would help them as they developed their own escape room.

Skills taught: Interviewing, researching, communicating, listening

Step 2: Creating teams. Students organized themselves into teams. Everyone had a job. They elected a manager to oversee the project. The teams each took on different components, or puzzles, in the escape room. The manager set checkpoints throughout the process to make sure everything was on track and that teams were collaborating effectively with each other.

Skills taught: Teamwork, leadership, delegation, communication

Step 3: Presentation. The teams each presented their puzzle ideas to the rest of the group and to the teachers. They fielded questions about how the puzzles would work, including the inputs, output, and how their puzzle would connect to the other puzzles.

Skills taught: public speaking, presentation skills, communication, listening

Step 4: Prototyping. We work with a partner called the Beam Center, a nonprofit organization in Brooklyn, that helped students with the construction and technology behind the escape room. Students created a prototype for each puzzle. One student built an enigma machine, an encryption device used to encode and decode secret messages. The students coded it so when visitors dropped a coin into the machine, it would give them a digital code. That feature made it more interactive and fun.

We used Arduino microcontroller programmable circuit boards. Arduino circuit boards are able to read inputs such as a light on a sensor. The circuit boards were embedded in the various puzzles to open latches, control motors and light up LEDs in response to sensors being activated by participants.

For instance, a student painted a picture of Dracula and the Beam Center put sensors inside the painting. When players held a cross near the painting, a light in Dracula’s eye would turn on. If they held a stake and garlic near it, it activated the painting to move down to let them access another part of the puzzle. Students installed cameras and a sound system so they could watch players and deliver clues.

Skills taught: problem-solving, teamwork and technical skills (coding, art, carpentry, etc.)

Step 5: Testing and reflecting: Once the prototypes were made, the teams tried each other’s puzzles and provided feedback. The feedback and reflection is incredibly important in project-based learning because it helps students practice providing (and accepting) constructive feedback to help them improve.

Skills taught: communication, listening

Step 6: Final presentation: Once the escape room was finished, we set it up as an open house and continued to make improvements based on how players interacted with the different puzzles. Students watched how everyone interacted with it. The adults were careful about touching things. Little kids tore through it, which helped students improve the design to make it sturdier. Students interacted with the public to share their project

Skills taught: presenting, public speaking

What we learned

From an instructional standpoint, we wanted to teach both academic lessons as well as essential skills such as collaboration, communication, leadership and problem-solving as a team. This project checks all of those boxes repeatedly.

Academics: This project helped students understand the “Dracula” story in more depth, supporting our academic objectives.

Nonacademic competencies: Students learned how to work together as a team to make their puzzles interact. They had to communicate, listen to each other, provide feedback, reflect on it and grow so they could improve their project.

We noticed something especially amazing: This project really created equity for all students. You would not have been able to tell who had an IEP and who didn’t. Everyone was an equal partner. This project gave all students an incredible opportunity to succeed, use their voice and develop skills that will serve them well for the rest of their lives.

Career tech skills: This project was also amazing for teaching hard skills such as coding, woodworking, engineering, construction and more. It also taught productive struggle. For instance, after observing that a project was too difficult, the students updated it but made it too easy. People were cheating and finding ways to get through the room without completing the tasks properly. It required several tweaks, but it finally reached a really good level where it was challenging in different ways for all ages: adults, high-schoolers and elementary students.

Engagement: The project engaged students on a far greater level than traditional classroom instruction typically does. It improved their ability for what we call design thinking. In designing this project, they had to prove why it was needed, prototype it and present it.

This project really hit all of the elements of Gold Standard PBL, and we’re so proud of the students for how it turned out.

For any districts interested in creating an amazing project-based learning experience like this in their school, here is our advice:

- Get buy-in from school or district leadership. In our case, our principal is a huge advocate and is good at making sure he provides teachers with the opportunity to design what they want to design. This support is important.

- Start small. You don’t have to build a full escape room. We are currently working on an escape room without walls, where the puzzles are on tables and you solve one to move on to the next. That’s an example of how you can do a lot with less.

- Training. Make sure all teachers have gone through project-based learning training. This will help make sure teachers understand how to tackle PBL, and will increase their comfort level with it in the classroom. At our school, all teachers are trained, and we have four PBL coaches at the school. This has allowed us to do amazing things.

- Involve students. Put them in charge as much as possible. Have them come up with the idea. Ask them to identify the problem, prove it exists, brainstorm solutions and attempt to build something to address it. Anything can be built into that spectrum.

- Focus on students’ strengths. Try not to have the project revolve around your strengths as the teacher. Make it revolve around students’ strengths. Step away and let them run with it.

Our escape room was a big, involved project with huge results. Students learned leadership, teamwork, problem-solving skills and more. Future plans may include partnering with an elementary school to design an escape room. We’ve also discussed using an escape room project as a fundraiser. The possibilities are endless.

Any project-based learning project can have similar results when done right. Put students in charge, coach them along the way and watch what happens. They will do amazing things.

Philip Baker and Danielle Ragavanis are teachers at the Thomas A. Edison Career and Technical Education High School in the Queens borough of New York City. They received professional development in project-based learning from the nonprofit PBLWorks. Their school was named the 2022 School PBL Champion by PBLWorks for its unique approach to turning project-based learning into a schoolwide strategy.

Opinions expressed by SmartBrief contributors are their own.

_________________________

Subscribe to SmartBrief’s FREE email newsletter to see the latest hot topics on EdTech. It’s among SmartBrief’s more than 250 industry-focused newsletters.